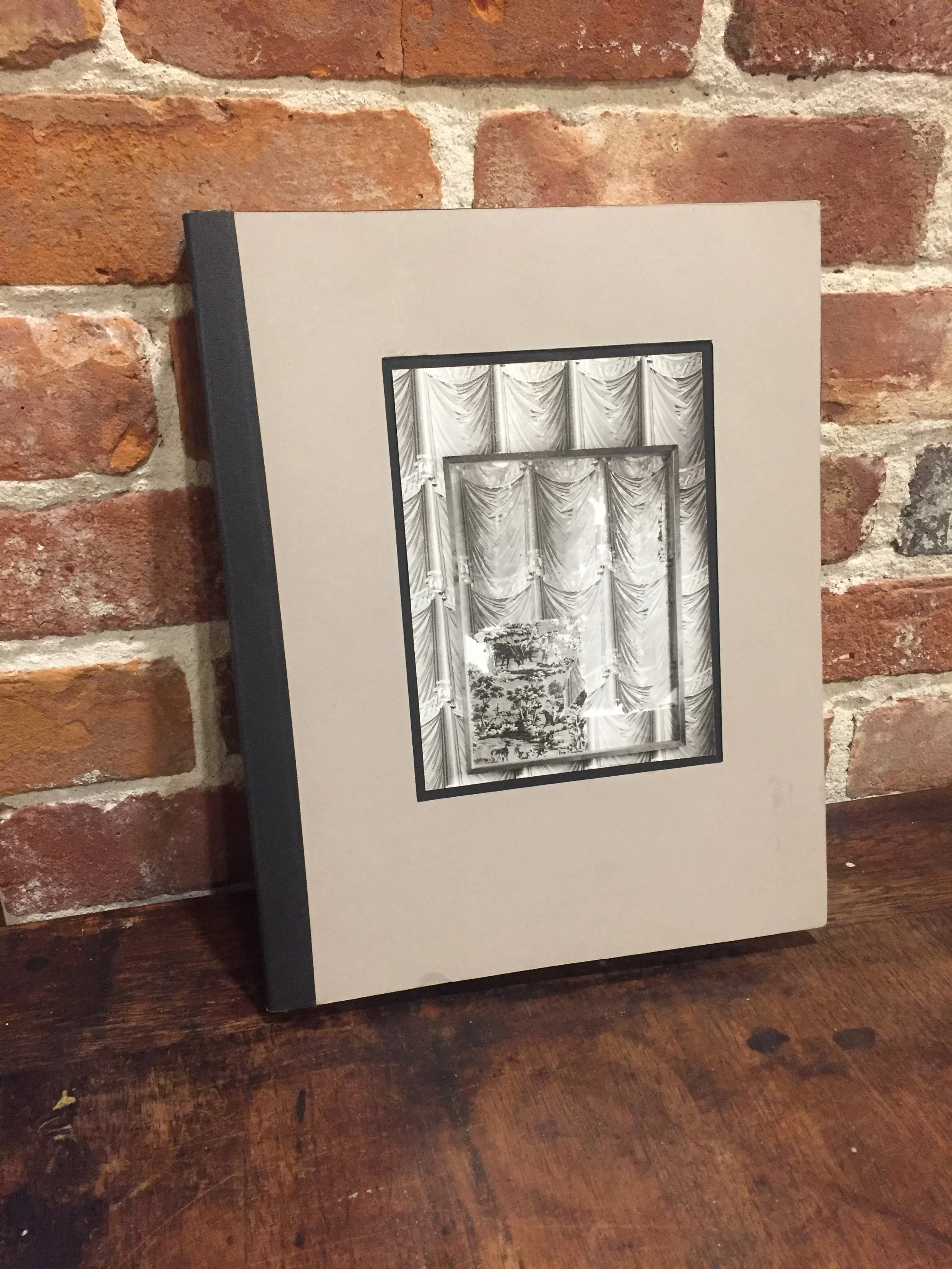

Go to the Land and I Will Show You : Alana Perino

PC: Alana Perino

Andrew D. McClees (ADM): For those who aren’t familiar with you, or your work, could you introduce yourself?

Alana Perino (AP): I'm a photographer but also broadly a lense based artist. My practice and my work is occupied with the reconciliation (or lack thereof) of self, home, and belonging.

ADM: I've never been super clear on what a lens based artist is, I'm familiar with photographers, filmmakers, videographers, etc - but "lense based artist" is a label or classification that I've never quite wrapped my brain around, mostly due to lack of explanation. Could you fill me in on what defines a lens based artist, and possibly relate it back to your own work and practice?

AP: I’m glad you asked this question because I have been grappling with how to define myself as an artist lately. I fall back on the classification of “lens based” as a means to say that I work with cameras. Film cameras, digital cameras, videocameras etc. But the truth is that I’ve also been engaging with collage, casting, and installation for some time now. I don’t feel as proficient in these other fields, but one day I’m hoping to consider myself as an artist who is not media specific. Till that time comes, I use lens based to define the kinds of tools I engage with, tools with lenses.

ADM: We’re talking about your upcoming photobook project “Go to the Land and I Will Show You” - how did you start your project? And where did the title come from?

AP: I began the project on a road trip from New York to California. I had wanted to stop to see Gettysburg on the leg from Philadelphia to DC but no one else in the car was interested. We passed many heritage sites in that same fashion and I suppose I became a bit obsessed with them. After that trip I made 11 road trips over the span of 8 years to specifically see "American" heritage sites. I was interested in the struggle of trying to experience invisible histories and the ways that landscape creates collective memory. More specifically I was interested in photographing the illusions of how history imprints itself or is imprinted upon landscape. The title comes from the Bible. In Genesis, God commands Abraham to leave his home and go to a land that will be shown to him. Obviously there are many translations of this Hebrew text, but I chose this version. It felt particularly relevant to the United States mythologies that justify settler colonialism, indigenous genocide, manifest destiny, and the mechanisms that engage with tourism in the US.

PC: Alana Perino

ADM: 11 road trips over eight years is a major endeavor - I'm sure you've seen almost every major site (official and unofficial) at this point - however, did you find yourself gravitating more towards a specific set of sites, and were there any sites that you came away from either with a new understanding of American history, or that you found yourself making especially significant (to yourself, or otherwise) images at?

AP: There are so many historic sites, I’d argue that the functioning of American culture is very much embedded in the designation and curation of these sites. It’s impossible to see them all, but yes I’ve many of the “major” ones. Truly it was an obsession which began on my first road trip in 2013. I was with some friends who were less inclined to stop at these sorts of places. They were more interested in seeing friends and family. Gettysburg was on our trajectory but we didn’t stop there. My father isn’t a Civil War fanatic but he is emotionally invested in 1993 film about the battle. We used to watch it together when I was young. He knows every line. I had always wanted to go there, to situate my body where I had seen the bodies on screen, where the historic bodies descended on the hills or fell in the fields. When I finally went to Gettysburg, it was a culmination of that desire that was quite anti-climactic.

ADM: The project has undergone several really fascinating evolutions over the time we’ve been in class together - what’s influenced the changes in the book?

PC: Alana Perino

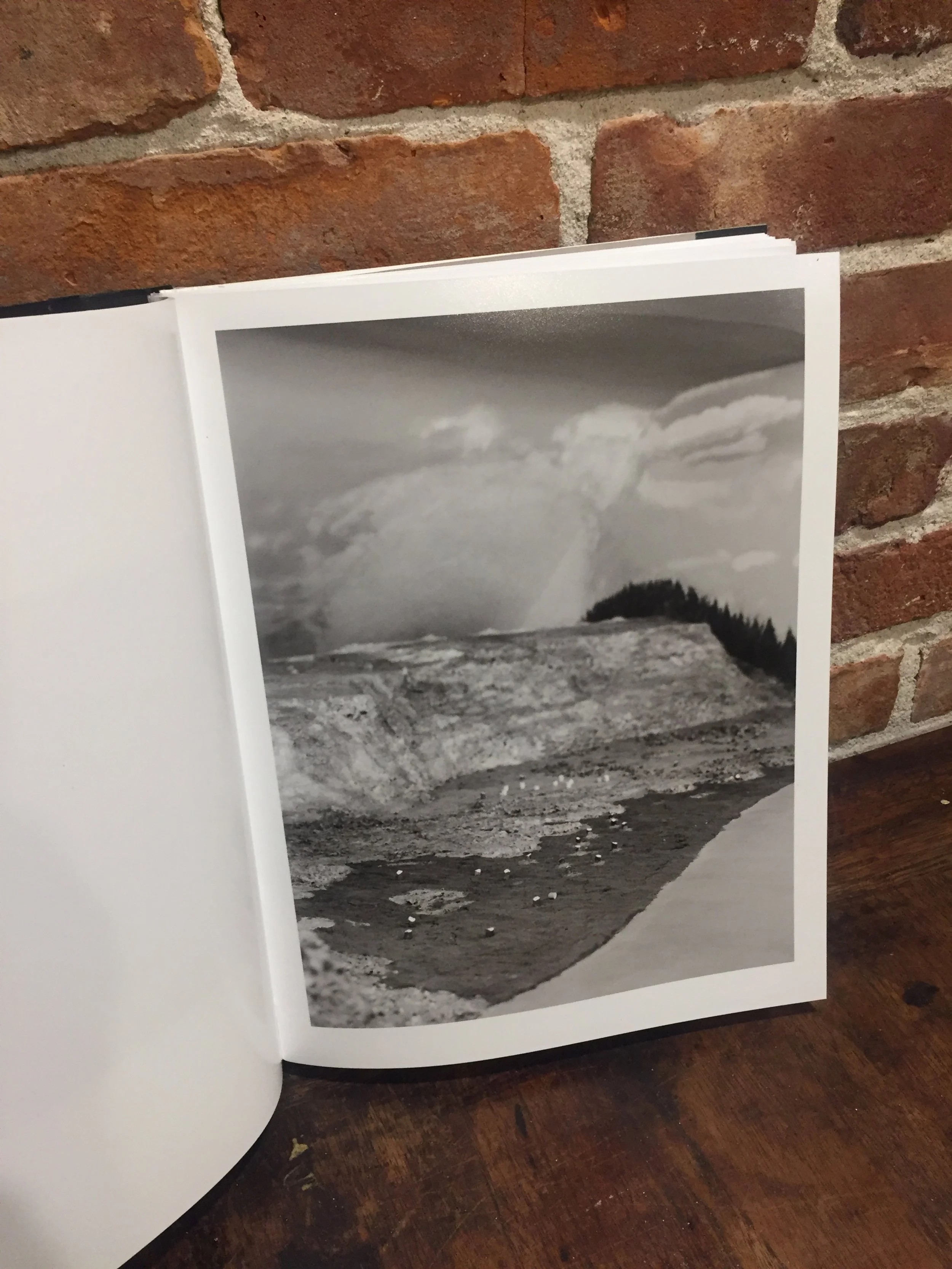

AP: A lot of the work I made over the years were nods to various photographers who engaged with the US landscape: Ansel Adams, Lee Frielander, Joel Sternfeld, Mitch Epstien. The editing process has mostly been a matter of distilling the work into a very specific vision, one that attempted to avoid the influences of other artists and relied on a personal conception of what these places look like. After a while it became clear to me that I wasn't even trying to tell a narrative as much as create an optical experience that triggered notions of place, memory, and history. The decision to not name the sites in the book felt crucial in this way, because it wasn't important to divulge where the pictures were made. It was only important to make the reader want to know, to question, and to want to see more.

ADM: When making photographs for the book, was there a particular thought process, or a specific intuition you followed?

AP: I suppose I photographed whenever I felt like I couldn't really see. The frustration would drive me to try to visualize in a different way, around a corner, through a viewfinder, from a different perspective. In this way, many of the photographs included in the book are instances of my seeing unsuccessfully, and the images where I achieved a certain amount of visual or narrative satisfaction were left on the cutting room floor. Seeing became a metaphor for knowing, for experiencing, and I wanted to create a world full of the unknowable and the unseen.

PC: Alana Perino

ADM: That's really fascinating - it's sort of like digging into the subconscious of American history - the "silent" history if you will? - are there particular aesthetic notes or semiotics you find yourself using or returning to (if you're not actively considering them at the time of shooting) for that take on history, and "seeing the unseen?"

AP:I think a lot about orientation, disorientation, and the ways in which our bodies and senses are engaged when we encounter these sites. I focus on sight as the locus of that kind of experience. There is a colonial emphasis on “discovery” at most of these locations, which suggests the possibility of a direct observation of the past. The suggestion being that if you stand in such a way on a certain mound of dirt, engaging your imagination and the “knowledge” of history that’s been offered, that you can have an experience in time and space that moves you to forget when and where you are presently. I suppose a lot of my photographs are trying to visually engage with this kind of exercise, and what I settled on more than anything is the impossibility of that experience.

ADM: What projects are you taking on next? What's fascinating to you outside your book?

PC: Alana Perino

AP: Most recently I’ve been engaging with personal histories and my relationship to family and home. I’m specifically interested in how inherited trauma is stored in objects, space, and ultimately the body. The first chapter of the work which I call “Pictures of Birds” focuses on my father’s side of the family in Longboat Key, Florida. The second chapter, tentatively titled “Adult Children,” is an exploration of my relationship with my mother. For these bodies of work, I am expanding my practice to include installation, sound, sculpture, and collage but the work is still essentially photographic in nature. It’s all very experimental at this point which means I’m not sure what shape it will take in its final form, but I’m finding that unknowability very exciting and generative.

ADM: Over the course of your investigations into the American Landscape via placing yourself in historical sites, what did you learn?- beyond what's pictured in the book, either about yourself or about the photographic process - that you'd be keen to pass on to others.

AP: Rest became something that I had to actively entrench into my practice, not just as a respite for carrying a camera or walking in the hot sun, but as a mode of engaging my body and mind in ways that exercised other muscles. This was not something I practiced in the first few years of this project but by the end it was essential not just to the work but to my well-being as an artist and a person.

ADM: From Eric Kaczmarczyk: What does a day in the life as a photographer, as an artist, as a person, look like for you? What time do you wake up, go to sleep? Outside of photography, what are some of your favorite hobbies?

AP: I work best at night. I've always wanted to be a morning person but I've come to accept that my "morning hours" will always be closer to 1am, 2am, 3am, 4am, than 5, 6, 7 or even 8am, which is when I'm usually asleep. Late mornings and early afternoons are for meetings, paid-work, shoots, grant applications, sometimes rest or play. Evenings and nighttime are for my practice, and hopefully in the midst of all that I remember to eat dinner.

ADM: What question do you have for the next photographer? - you can answer your own question if you'd like.

AP: I'm always curious as to how other photographers know when a project is finished. For me, I can feel it in my body as a resistance to photographing. I become tired more easily, less motivated. It's very much a physical sensation as opposed to a mental or intellectual fatigue. This is how I know it's time to try something new.

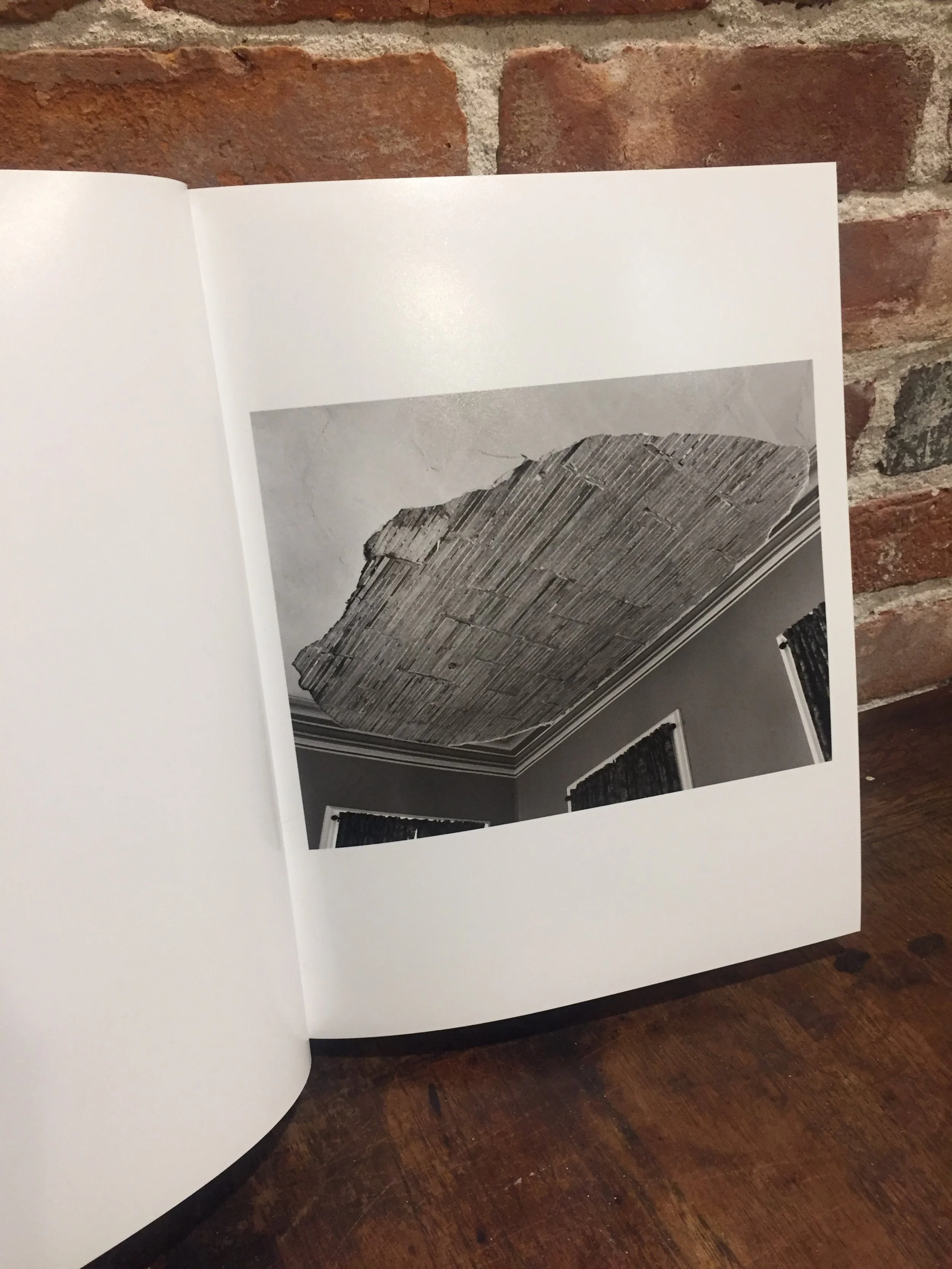

Gallery to the above left contains images of the current maquette of “Go to The Land And I will Show You”

ADM: Do you have any parting words/shoutouts/recommendations?

AP: We don't have a solid ETA yet but I will be publishing Go to the Land and I Will Show You with Drew Leventhal under his incipient publishing house, Valley Books. So keep a lookout for updates on this and other titles he'll be publishing in the very near future.

ADM: Awesome! Looking forward to buying my copy when it’s out in the wild!